After

Boulogne had fallen and France had surrendered to the occupying forces,

Sister Leplat, Sister Superior of the Boulogne Community wrote to the

Superior General at the Mother House in Paris:

Sister

Marie-Marthe, Sister Marie, Sister Jeanne and the young girls went to

London where they were interned for two months before spending eight

months in a beautiful large house provided by the government. During

air raids they gathered round a grand piano and as one of the

Sisters played they sang aloud to drown the noise of the attacking

planes and keep their spirits up.

When London became too dangerous the children and the four sisters and two young teachers, Renée Mottot and Thérèse Toulotte, were sent to the Smyllum Park Orphanage in the small town of Lanark midway between Glasgow and Edinburgh in Scotland. The orphanage looked like a castle and had its own farm, a school and was set in many acres of land. It was run by the Daughters of Charity in Britain but the young French children remained in the care of the French Sisters. They were told that the big house had been the castle of William Wallace but the truth was less romantic. It had been built about 1760 for Dr William Smellie (1697-1763), a renowned gynaecologist.

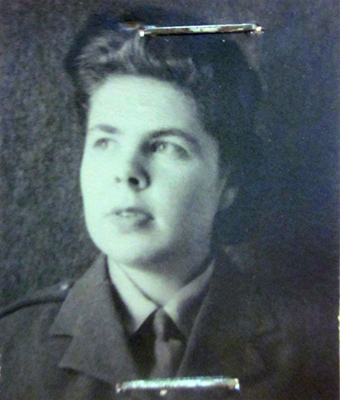

The older children grew up and became young women while living at Smyllum. Two

of them joined the Free French Forces in Great Britain. Julienne

Blondeel (the photograph, right, was taken in 1944) was 14 years old in

1940 and had lost her father the year before. Andrée Daguebert was 17

years old and had lost her parents in 1934. She was an apprentice sewer

in the orphanage. When the girls arrived in Scotland, Andrée remained

with the others, helping the Sisters to take care of them. She then

worked for French priests before becoming an apprentice nurse. During

the summer of 1944, both girls, aged 18 and 21, enlisted in the Corps des Volontaires Françaises, the female unit of the Free French Forces in Great Britain.

The older children grew up and became young women while living at Smyllum. Two

of them joined the Free French Forces in Great Britain. Julienne

Blondeel (the photograph, right, was taken in 1944) was 14 years old in

1940 and had lost her father the year before. Andrée Daguebert was 17

years old and had lost her parents in 1934. She was an apprentice sewer

in the orphanage. When the girls arrived in Scotland, Andrée remained

with the others, helping the Sisters to take care of them. She then

worked for French priests before becoming an apprentice nurse. During

the summer of 1944, both girls, aged 18 and 21, enlisted in the Corps des Volontaires Françaises, the female unit of the Free French Forces in Great Britain.

The story of HMS Venomous is told by Bob Moore and Captain John Rodgaard USN (Ret) in

A Hard Fought Ship

Buy the new hardback edition online for £35 post free in the UK

Take a look at the Contents Page and List of Illustrations