Pierre

Ratcliffe was only five years old when he left Calais on HMS Venomous

with his parents, Albert and Renée Ratcliffe, his sixteen year old

half-sister, Gisèle, and their young cousin, Jack Ratcliffe. Albert

was born in Calais in 1891; he was the son of a colliery engineer from

Wakefield who came to France with his company in 1889. Albert was one

of eight children and served in the British Army with the Machine Gun

Corps during the First World War. He worked in Calais for an

American company exporting lace. Albert's first wife died of

tuberculosis leaving eight year old Gisèle without a Mother. Renée's

parents had emigrated to

America and she was born there in 1911, but they returned to France in

1933 during the Great Depression and she married Albert in 1934. The

family had British passports.

Pierre

Ratcliffe was only five years old when he left Calais on HMS Venomous

with his parents, Albert and Renée Ratcliffe, his sixteen year old

half-sister, Gisèle, and their young cousin, Jack Ratcliffe. Albert

was born in Calais in 1891; he was the son of a colliery engineer from

Wakefield who came to France with his company in 1889. Albert was one

of eight children and served in the British Army with the Machine Gun

Corps during the First World War. He worked in Calais for an

American company exporting lace. Albert's first wife died of

tuberculosis leaving eight year old Gisèle without a Mother. Renée's

parents had emigrated to

America and she was born there in 1911, but they returned to France in

1933 during the Great Depression and she married Albert in 1934. The

family had British passports.

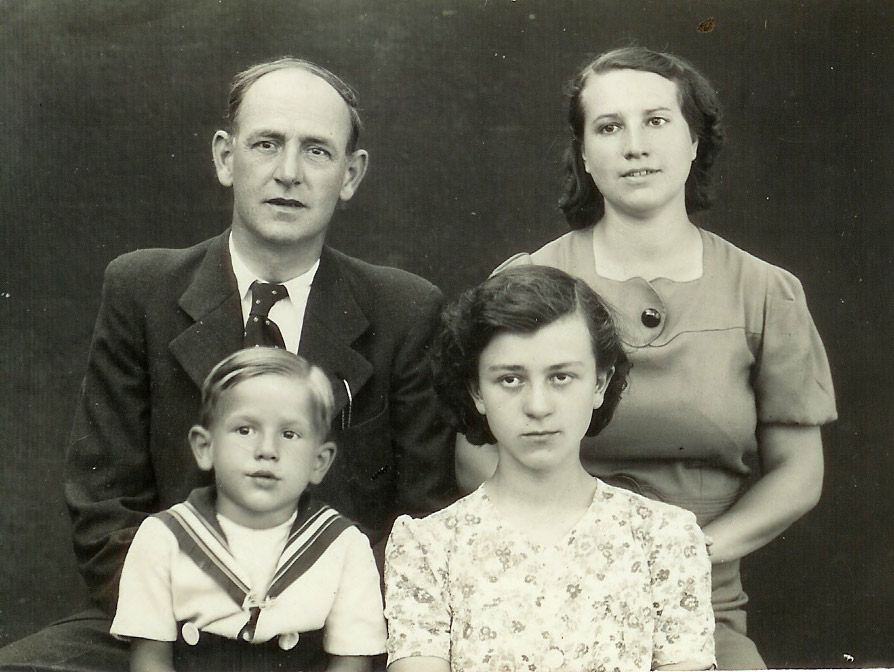

Albert Ratcliffe with his his young wife Renée and his son, Pierre, and daughter, Gisèle, in Calais before the war

Courtesy of Pierre Ratcliffe

Much later in her life Gisèle described events in the days before they escaped to England on HMS Venomous and the problems they faced on arrival in England finding work and somewhere to live.

"My

memories of events in May 1940 are a bit vague. I remember some stupid

things clearly but important events are often half forgotten. We lived at 31, Rue du Jardin des Plantes in Calais. There

were one or two air raid alarms at the beginning of May but nothing

serious until the 10 May when Belgium and Holland were invaded. I

remember waking up that morning and seeing my parents looking out of my

bedroom window. I had slept through it all!

We decided to move to Sangatte to a cottage we had rented. I traveled

daily by bus from Sangatte to Calais to attend the secondary school

which was near the town hall. If there was an air raid alarm, the whole

school was taken to the town hall until the 'all clear' sounded. Yvonne

Sabau and her mother were already in Sangatte and so were the

Vanpouille family. One day, I was doing my homework in our cottage,

when a sea mine exploded, which damaged the roof at the back of the

building. Yvonne and her mother left their cottage in Sangatte to

travel south. Some people had already left the village. Following

Yvonne and her mother's departure we went to live in their home.

British

and French soldiers, RAF personnel and some British sailors were

billeted in the village. On about the 21 May, the Vanpouille who lived

next door, woke us up to tell us that the Germans were not far away. We

collected a few belongings. My Mother and Dad cycled with five year old

Pierre on a bike seat while I got a lift with a farmer. The road was

crowded with people going south - in cars, on bicycles, or walking and

pushing prams or wheelbarrows with their belongings. When we got to

Calais, I noticed there were queues outside some shops. We went to

Pierre's gram'ma while Renée, my Mother, went to the British Consulate

to see if there were plans for the evacuation of British subjects. Dad

went to our house to collect passports and a few items of value. Uncle

Harold, Dad's brother, was contacted but said they could not leave because their son,

Allen, was in Escalles. Jack Ratcliffe was there, having cycled from

Dunkirk on a stolen bike. Uncle Edmond was also told of our departure

and gave us a lift to the harbour. There was a ship evacuating British

citizens.

When

we arrived at the harbour an air raid was in progress. There were

already signs of bomb damage. We crawled under a train to shelter then

finally made it to the ship. As the ship left the harbour, I saw Allen

arriving empty handed on a bicycle and looking dejected. Most people

stayed below deck. Jack kept going up on deck as he wanted to see the

harbour taking a battering. I remember a woman being very worried

because she had left some washing on to boil. I can't remember if we

landed at Dover or Folkestone.

The

organisation on the other side of the channel was marvelous. The

authorities were ready to receive us. There were questions to be

answered and passports to be checked. The WVS (Womans Voluntary

Service) was of course there. These splendid middle class English

ladies were dishing out tea and food. They all smelled of lavender!

We went by train to London and were taken

to a large terraced building. I still don't know where it was. There

were a lot of refugees like us. We were fed and given blankets and

slept in our clothes among all these people. In the morning we were

given breakfast. Dad had a chat with a civil servant and told him he

had a sister in Leeds. I've no idea if Dad had enough money or if he

had to pay for anything, seeing we left in such a hurry. We went to

Leeds by train. Auntie Pattie, Uncle Jack and Gram'ma were very

surprised when they opened their door to us. They seemed to have no

idea that conditions were so bad in France. Pierre went out into the

street. Being a chatterbox he was soon talking away in French to a

group of children. He came back in the house and announced that all the

children were deaf.

Auntie Pattie and Uncle Jack agreed to

young Jack, our cousin, living with them. A few days after our arrival

in Leeds we went to Nottingham where Dad I think had some contacts

through the lace trade. We were in rooms in Arnold. No luck there for

Dad. We came back to Leeds and rented some rooms in Meanwood. I can't

remember how but eventually, after leaving Leeds once more, Dad got a

job in Newark-on-Trent. He was talking to a bus conductor, telling him

he had just got himself a job but had no idea where he and his family

were going to live. The bus conductor generously said we could come and

stay with him and his wife. We all moved to the bus conductor's house

in Newark.

They were a very young couple, newly married, the wife was only

nineteen. The furniture in the house was minimal - I think we slept on

camp beds. They were kind and generous but it was far from being an

ideal situation.

I went to the local primary school so I

could improve my English. Being sixteen, I felt out of place but the

teachers were kind and understanding and used to take me aside for an

hour or two to teach me. The children were lovely and it used to amuse

me to hear them sing.

It was difficult for both families at the bus conductors house, a

small three bedroom council house. Something had to be done. I have a

feeling they didn't know what to do. Renée being born in the USA was

eligible for repatriation. She thought that if she went to the States,

she could get Dad a job at the head office of Stern and Stern - that is

what I understood at the time. She decided to go with Pierre.

Dad and I moved. We rented rooms with the

use of kitchen a few miles outside Newark-on-Trent. The lady of the

house lived there with her young daughter. I think her husband was in

the forces. I enrolled at the technical college to study English, life

drawing and dress designing. We missed being a complete family.

Saturday we went to the cinema and had fish and chips for supper. Dad

used to buy a large bottle of cider; we drank that after supper. He

used to tell me that it wasn't alcoholic but of course it is. Life was

not easy in the States. There was no job for Dad. After eight months,

Pierre and Renée came back.

We went back to Leeds and Dad got another

job. We rented a flat above a shop in Meanwood. And eventually we moved

into a house. Life became easier. Renée got a job and I started work in

a chemist shop. I remember I was paid 17/6 a week. Pierre was at school

and we were not far from Auntie Pattie, Uncle Jack and Gram'ma.

I personally felt I ought to do something

for the war effort. I did not want to be called up for the forces and I

certainly did not want to go into munitions work. I remember girls who

worked in munitions factories coming into the shop; some of them had

jaundice due to the materials and chemicals they used. I rather fancied

the open air and the countryside and all being well, perhaps nursing

later on. I noticed all the land girls looked fit and well.

On my eighteenth birthday on my afternoon

off from the shop, I went to town and enrolled for the Land Army. I

only told Auntie Pattie. I was declared physically fit to work on the

land by the local doctor and in September I was off for a month

training at an agricultural college."

Gisèle enjoyed her years working as a Land Girl near Lake Bala in

North Wales and Pierre remembered visiting her on holiday during the

summer of 1944:

"There

were many girls there at the hostel where they stayed and I loved it

... being tucked in bed by the girls, especially Rosemary. Rosemary and

Gisèle were great friends ever after. Rosemary came to Calais after the

war ... They were looking for young men to marry!"

The

Women’s Land Army and the Women’s Timber Corps, known as the Land Girls

and Lumber Jills, worked on farms to feed the nation and fell timber,

as the men went to war. At its peak in 1943 there were some 80,000

women working on the land, and it was continued after the war, finally

being disbanded in 1950.

Gisèle trained as a nurse in Bradford and when the war

ended she remained in England and became a nurse in York. She married

Edward Richard Mack a civil servant in the army ordinance corps. They

moved to Nottingham then went to Aden for four years and on returning

to England lived in London. Gisèle died on the 9 December 2011.

When Albert and his family left Calais for England aboard HMS Venomous he left behind three brothers who had fought for Britain in World War I. Harold Ratcliffe was born in 1898 and was eighteen when he enlisted in 1916. After the war he managed the co-operative wholesale society in Calais (la Coopérative Anglaise) founded by his father. In July 1940 he was arrested by the Germans, imprisoned in Lille and at Huy Fortress, Belgium, and finally at Tost (Toszek) internment camp in Upper Silesia but survived to return to Calais. His son, Allen, was active in the Resistance, was captured and died of typhoid in Dachau. Frank was a year younger and enlisted in 1917, was badly gassed and was an invalid for the rest of his life. In July 1940 he was living at Malo les Bains with his wife and two children. He was an active member of the British Legion and helped destroy equipment left by the BEF so that it did not fall into enemy hands. He was arrested by the Germans and imprisoned in Lille but as a war invalid was set free on parole but had to report regularly to the German authorities. He died in 1944 in Lille. Allen born in 1895 also fought in the Great War and afterwards lived in Paris where he worked for an American art gallery. In 1940 he fled to the "Zone Libre" in the south of France to avoid being arrested. His wife and daughter stayed in Paris. He had also been severely gassed in the Great War and this contributed to his death from tuberculosis in May 1945 . All three brothers were born in France but under French law were allowed to take the nationality of their father. They had British passports and could have left Calais for Britain.

Pierre

Ratcliffe's older cousin, Jack Ratcliffe, joined the RAF towards the end of the

war. He married in England, had a baby girl and after working as a salesman

became a French teacher at a school in Leeds.

By

the time the Ratcliffe family returned to Calais from Britain in

January 1946 Pierre, the little chatterbox who knew no English had

forgotten his French, but he was a bright boy and soon caught up. He

entered the Ecole des Mines de Saint-Etienne in 1957 and graduated in

1960 and then had to do his two years of military service before he

began a successful career as a mining engineer. His

wife's family also came from Calais. They had three children and seven

grand children and live in retirement in Callian inland from Fréjus. Pierre Ratcliffe, the French son of a

French born British subject who fought in the British Army in the Great War and grandson of a miner from Doncaster, is

proud to have dual nationality. If

you would like to know more about the Ratcliffe family and events in

Calais after they left for England in May 1940 follow this link to his web site.

Return to the Evacuation of British citizens from Calais in May 1940

The story of HMS Venomous is told by Bob Moore and Captain John Rodgaard USN (Ret) in

A Hard Fought Ship