Tom Sarginson was born in Paris in 1896 and brought up in France by his French mother and English father.

His father, Bill Sarginson, was a tailor's cutter and his wife Jeanne, a Giletiere (waist-coat maker). Under

French law Tom took his father's nationality but grew up speaking

nothing but French and only learned to speak English when he

served in the Royal Flying Corps as

an electrical mechanic based near Rouen, Northern France, in the Great War.

He

looks very handsome in the photograph in his RFC uniform on the left

with his Aunt Marie and Cousin Suzanne at their home in Paris. His

parents returned to England during the war and Bill Sarginson died

there in 1920 and

Jeanne in 1931.

After

the war, Tom completed his apprenticeship in England as an electrical

engineer and came over to Calais in 1926 to help start

Courtauld's factory, Les Files de Calais SA, producing rayon, Soie Artificielle

(artificial silk). His English wife Nell followed him with their new

baby daughter Beatrice Marie. They settled in a house opposite the

factory, where a row of English style houses had been built for the

factory foremen (they are still there). Irene Marguerite was born in

1928 and Jeanne Elisabeth in 1932. Tom became the chief engineer, owned

a car, was respected by both the French and English and was a stalwart

of the British

Legion.

The caricature was drawn outside the Trocadero on a visit to Paris in 1933.

If you know where to look Tom Sarginson and his youngest daughter, Jeanne, who was born in France, can just be seen in the photograph taken on the 26 July 1936 when King Edward VIII unveiled the memorial to the Canadians who died on Vimy Ridge (he abdicated in December) and he is second from right in the photograph taken at Calais on the day King George VI and Queen Elizabeth left on the Royal Yacht after their state visit to France in July 1938.

King Edward VIII at Vimy Ridge on the 26 July 1936 on his only State Visit abroad and his younger brother King George VI at Calais in July 1938

Courtesy Jeane Gask

The youngest of his daughters, Jeanne Gask, tells her family's story below and more fully in a book to be published in May 2015 on the seventieth anniversary of the end of the war and seventy five years after the Germans occupied Calais and her father was interned.

*****************

"We three girls went to the College Sophie Berthelot (I went when I was five). We were brought up as French and all our friends were French but our nationality was British. Our father hired a cottage in Sangatte every summer, and moved the family there, while he commuted to work. Our English Grandparents (our Mother's parents) came over and stayed there with us. These were wonderful days playing by the sea with my dog.

Although

I was only eight in 1940, I still remember the names of some members of

the British community: Mr. Allitt, Mr. Hartshorn, the British Consul

and Mr. McCullagh, the church minister. Also Captain Masters, Captain

of the Cote d'Azur, the ferry between Calais and Dover, who let me take the wheel when I was about six years old! The Cote d'Azur was sunk off Dunkirk in 1940, salvaged and converted into a minelayer renamed Ostmark and sunk by the RAF in the Baltic in April 1945. I must have known Johnnie Eslemont who escaped from Calais with his parents on HMS Venomous. I remember the name but he was much older than me and his father was one of Tom's colleagues.

When the German invasion was nearing

Calais Tom was told that the last boat for England was leaving and that

we should go too, but Tom thought everyone was panicking and that we

should stay until it "blew over".

A couple of days later, Tom took the dog, cat and the chickens to

friends in the country, put two mattresses on the car roof for

protection in case of machine-gun bullets, tied the family tent to the

back bumper, packed the car boot with food and blankets, put us three

girls on the back seat and said, "Come on, we'll go camping in the

South of France", and off we went.

We

immediately found ourselves part of the exodus of cars, trailers,

carts, bikes and people on foot, all fleeing in front of the Germans.

Abbeville was on fire. Tom said, "Once we're over the Somme, at St.

Valery, we'll be free." But we never made it. We went round in circles

at Rue and sought shelter in the grounds of a farm at Quend, near Rue,

and stayed there a few days, sleeping in a barn and a cowshed, till we

were over-run by the German troops. We were allowed home after two or

three weeks. Tom went back to work, though he knew his days were numbered, and we girls went back to school."

The family was soon to be split up

George Gregson wrote in his Jounal on 18 July 1940

Tom

Sarginson was arrested in July 1940 and kept prisoner for several days in the

Salle des Marriages (where civil wedding ceremonies take place) at the Hotel de Ville, the most impressive and best known building in Calais.

The British community in Calais was a tight-knit group and the men all

knew each other and cheered as another one was brought in.

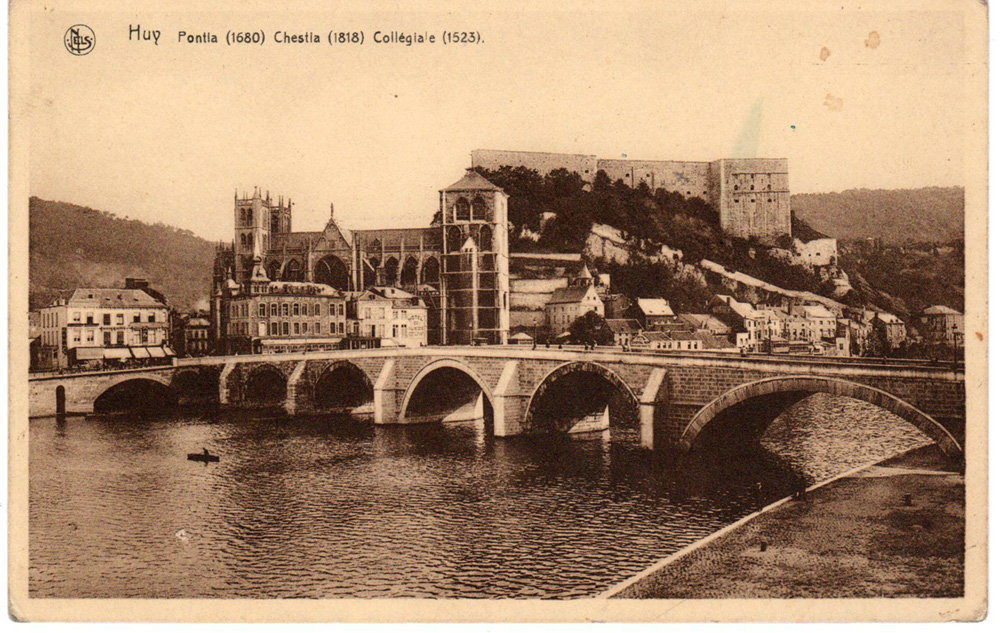

After a few days they left for Loos Prison in Lille and were then

taken to Huy Citadel in Belgium. It's here that P.G. Wodehouse joined

them.

He lived in Le Touquet, in Northern France with his wife Ethel.

There is a plaque on the wall

of the Citadel stating that P.G. Wodehouse was held there between

August and October 1940). I think they had a very rough time, Tom never

spoke of it.

They then went on a three-day train journey to Tost in Upper Silesia (now Totzak, Poland) where 1,800 men were interned at a former lunatic asylum, Illag (Internierungslager) VIII-H. Some of the Calais men managed to stay together in the same dormitory and eight of them sat together at the same table at meal times, together with P.G.Wodehouse. Tom didn't like him very much, found him effete and mannered. George Gregson gave their names in his Journal on the 2 March 1941:

"Well, I have changed my table after all and am now at the same as Wodehouse, Webb, Davies, Rainey, Sarginson, Dutnall, Youl, Pickard and Barryball. Much better in every way. Usual dreary Sunday – they are always longer than other days however."

Jeanne said "When

my mother heard that George was having mental problems, she loyally

refused to believe it: she said he was faking it, so that he might be

returned to England and could then rejoin his unit."

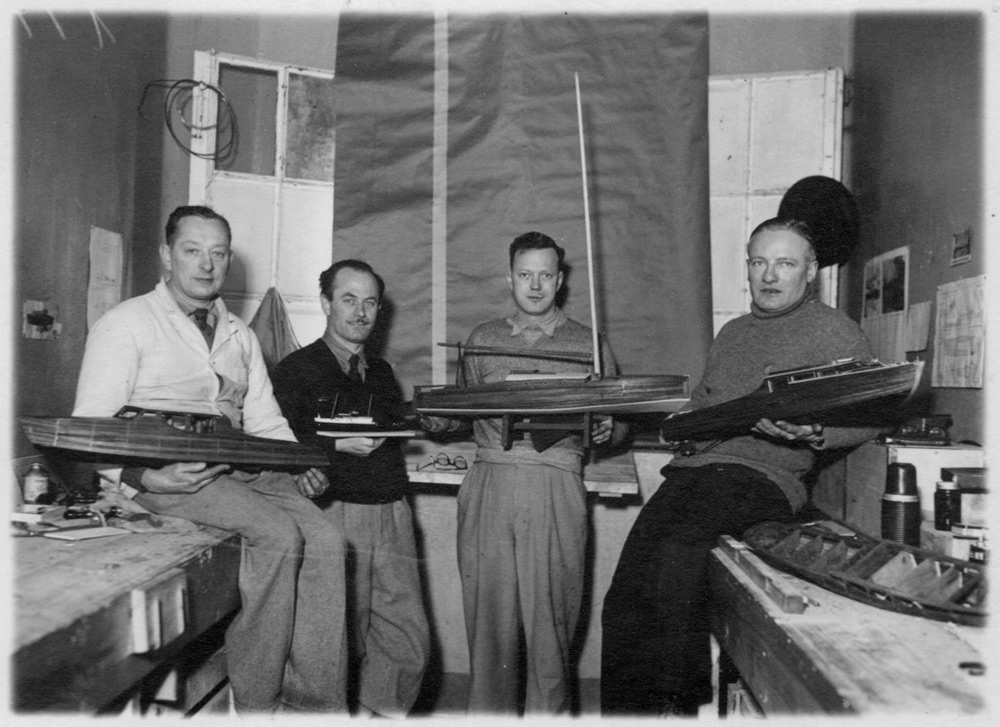

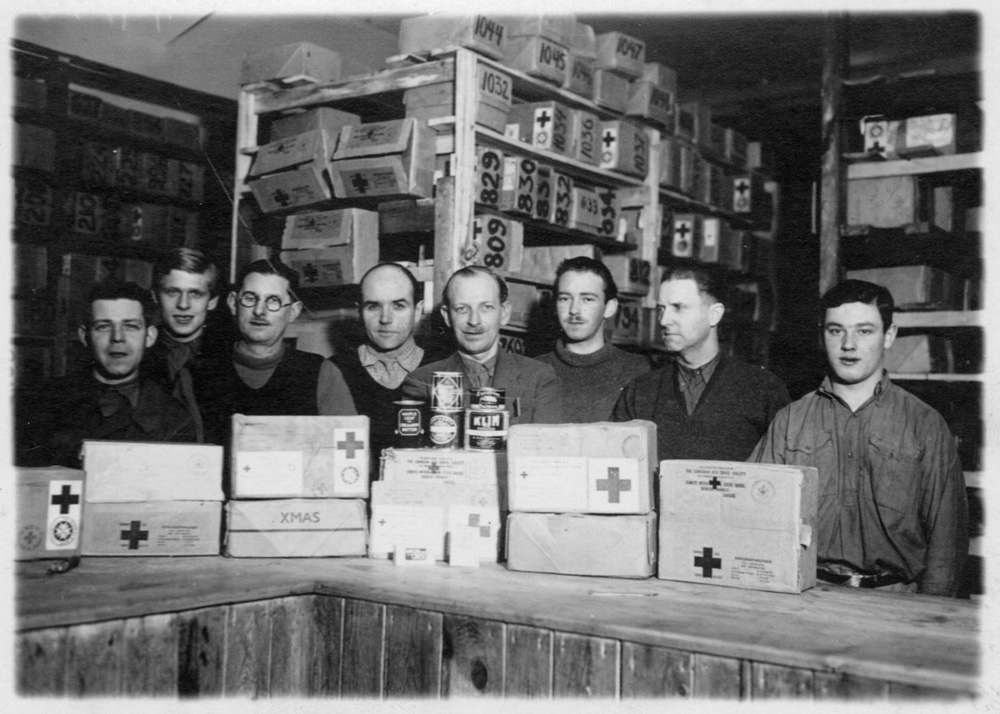

Tom Sarginson and some of his fellow internees at Ilag VIII-H, Tost, in Upper Silesia

Left:

Tom Sarginson always dressed imaculately and his appearance contrasts

sharply with the unidentified internee on the left who is casually

dressed, hands in pocket and smoking a cigarette

Right: From left to right, back

row: Sarginson, West, Gregson, Goard ; second row: Rainey, Yule, "Stock

Keeper SO" (name not given), Pegrum; third row: Pauline, Ernest

Dutnall, Harold Ratcliffe, Londoy

Front row: Perry, "chemist SO" (name not given), Lockwood, Larkin, Oliver Holding

Courtesy of Guy William Ratcliffe son of Harold Ratcliffe

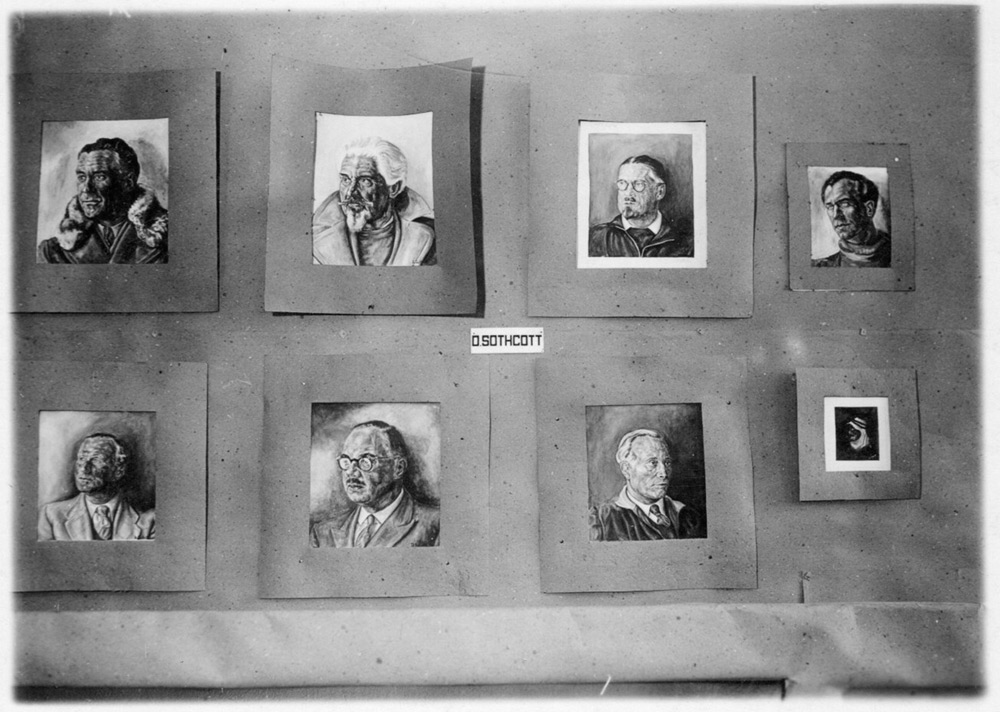

Tom decided that he would try and keep himself fit and busy. He was at different times Deputy Camp Captain, on the entertainments committee, on the sports committee, helped to build the dam, gave French lessons, made a couple of model boats, a cabin cruiser and a sailing boat, and passed his English School Certificate, his "Matriculation" ("French excellent"). He would walk round the perimeter each evening (four circuits made one mile).

Apart

from business men and employees of the War Graves Commission, all sorts

of other people with a British passport had landed in the camp. Tom

said there was even a boat-load of missionaries caught at sea! And

there were actors, performers who had been touring the continent who

hadn't gone home in time. Tom said that the shows they put on in the

camp were every bit as good as any shows he'd seen in peacetime. Tom sang a French

carol in the camp chapel at Christmas time, but on the whole preferred

to see the shows rather than participate. The head violinist in the

photo was very well known in Holland.

What happened to "Nell and the Girls"?

My

English mother and us three girls were arrested in July and taken away

by army lorry. Nell had been told that, since Irene and I were born in

France we were French and could be left behind in Calais, and she and

Marie, both born in England, had to go where the authorities chose to

take them. Of course, Nell wanted to keep the family together and any

thought of leaving half her family behind was preposterous. We stopped

for the night at Les Attaques on the 27th July 1940 and George Gregson

mentioned meeting us there in his journal.

My

English mother and us three girls were arrested in July and taken away

by army lorry. Nell had been told that, since Irene and I were born in

France we were French and could be left behind in Calais, and she and

Marie, both born in England, had to go where the authorities chose to

take them. Of course, Nell wanted to keep the family together and any

thought of leaving half her family behind was preposterous. We stopped

for the night at Les Attaques on the 27th July 1940 and George Gregson

mentioned meeting us there in his journal.

"About 2pm, we all got into a lorry and were taken to Les Attaques, where we found other English. We had been joined in the morning by Mr and Mrs Wesley, each 72 years old, from Sangatte and, one way or another, our party had grown to 14. At Les Attaques, we found others from Calais, principally women and children and including Mrs Yule and Mrs Sarginson. Germans gave us some tea in the evening. Slept pretty well though feeling doubtful about the straw." George Gregson.

Mae Youll was our next door neighbour in Calais, married to

Sandy. I have a vivid memory of George and Nell, my mother, sitting

with their backs to the wall, having a long whispered conversation into

the night, while us three girls slept on the floor.

We were held in an internment camp outside Lille for six weeks, then taken to Cambrai where the bottom half of a gloomy empty house was broken into and we were told to live there. Nell had a very difficult time with three growing hungry girls and little money but we could go to school. At first she had no idea what had happened to Tom; he wrote constantly but his letters didn't reach her until November 1940, and she knew no-one.

In

his letters Tom tried constantly to boost my mother's morale and to

help her with the upbringing of us girls. She, being an English woman,

removed from her comfort zone in Calais, had very bad time but her indomitable

spirit saw her through. After

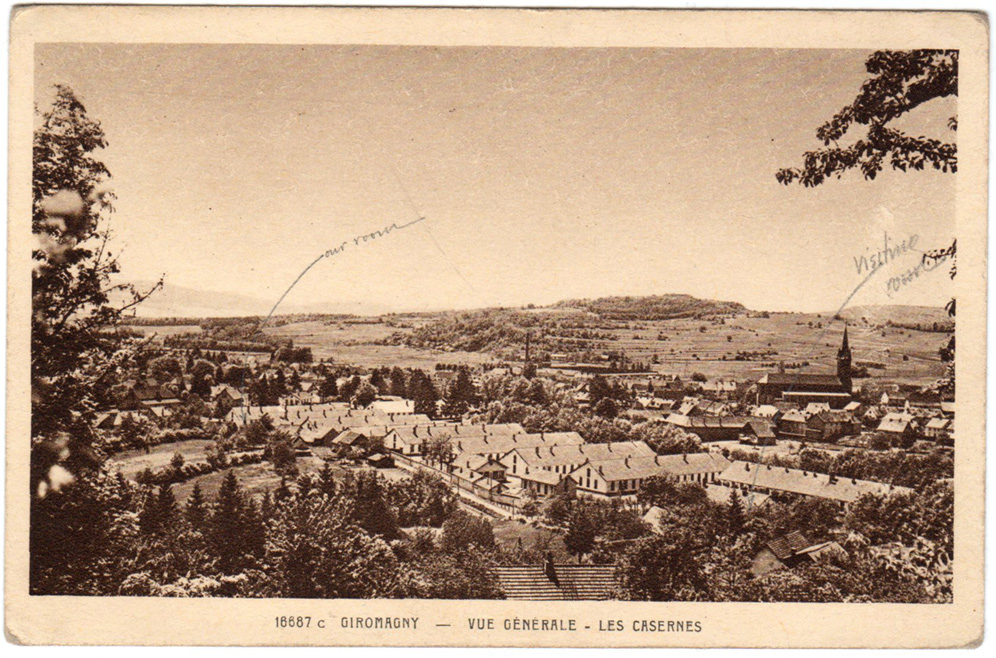

the internees were moved from Tost to Giromagny she was twice allowed

to visit her husband, facing difficult journeys as there was so much

bombing of railways.

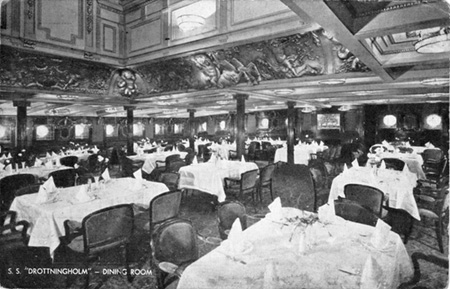

The men were repatriated in September 1944 when, after an horrendous journey through Germany,

they left Gothenburg, Sweden, on three cruise liners. Tom was on the SS Drottningholm,

the same ship that brought George

Gregson back from Portugal. When he finally arrived at his In-law's

house in Birmingham, there was no news of Nell and the girls.

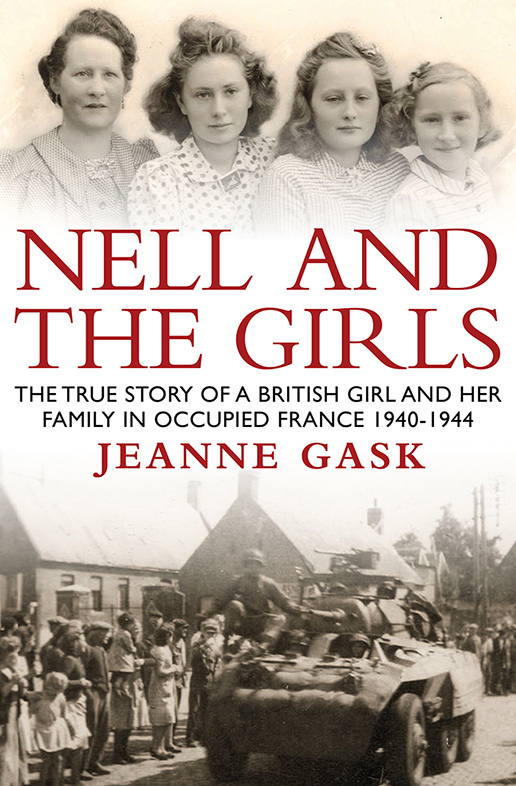

We were freed on the 2 September 1944 and flown home two days before Christmas to an emotional family reunion. I have tried to describe how we lived from a child's point of view in my book, "Nell and the girls".

Nell and the Girls: the true story of a British Girl and her family in occupied France 1940-44; by Jeanne Gask.

What happened to Tom?

After the war Tom went back to

Calais to help re-open the factory, but his heart wasn't in it. He

found it very difficult to get supplies delivered and get things going

again. Despite being highly respected in Calais where he was known to

everybody as "Mr Tom" he thought France the country where he was

born was finished and decided to return to Britain.

He sold his car and worked for

Courtaulds in Coventry until his retirement. He bought a plot of land outside Rugby and

inspired by reading an article in a 'Do It Yourself' magazine on "How

to build a £2,000 house for £1,000" he built his house for £998 and

spent his retirement growing vegetables. He died in 1964 aged 69.

*****************

Jeanne explained what happened to her Mother and sisters after their return to England:

"Marie joined the WRENS as

soon as she possibly could. On her demob, she became an Air Stewardess

for BOAC. She married a BOAC Flight Engineer and had three children.

She died in 1981, aged 55. Nell

died just before her 91st birthday in 1989. Irene became a Nurse, rising to Nursing

Sister, and married one of her patients. They had one child and lived in

Stroud, Gloucestershire. She is now aged 86. I never really settled

down, married Tony Gask and also had three girls. Lately, I became a

Blue Badge French speaking Tourist Guide and am now writing up the

family history."

Read about George Gregson's service in two world wars and his internment at Tost (Illag VIII)

Return to the Evacuation of British citizens from Calais by HMS Venomous in May 1940