Left:

Left: A studio portrait of Leslie Mortimer and friend soon after joining the Navy in December 1941

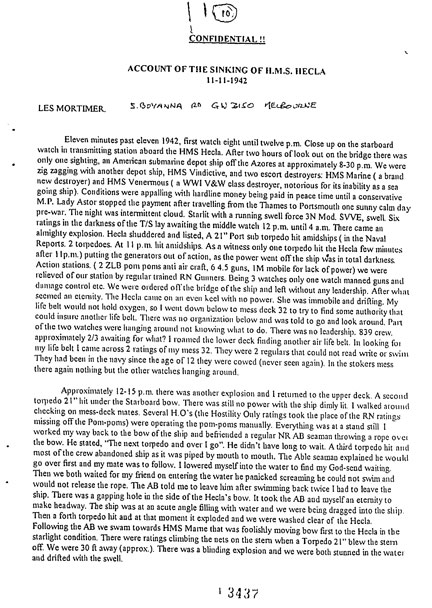

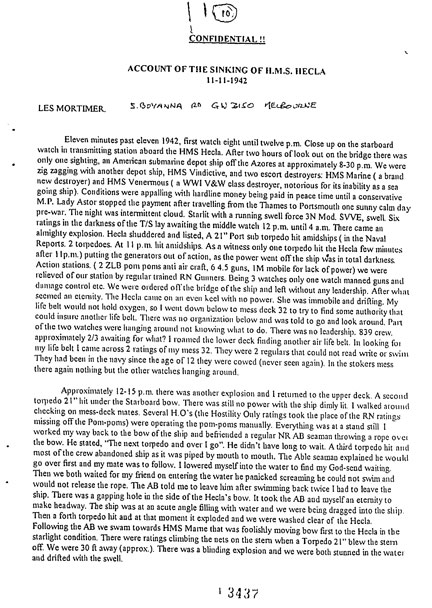

Right: The first page of his typed description of the sinking of HMS

Hecla and his rescue by HMS

Venomous on 12 November 1942

Eleven

minutes past eleven 1942, first watch eight until twelve p.m. Close up

on the starboard watch in the transmitting station aboard the HMS

Hecla.

After two hours as lookout on the bridge there was only one

sighting, an American submarine depot ship off the Azores at

approximately 8.30 p.m. We were zig zagging with another depot ship,

HMS

Vindictive, and two escort destroyers: HMS

Maine (a brand new destroyer) and HMS

Venomous (a

WWI V&W class destroyer, notorious for its inability as a sea going

ship). Conditions were appalling with hardlying money being paid in

peace time until a conservative M.P. Lady Astor stopped the payment

after travelling from the Thames to Portsmouth one sunny calm day

pre-war. The night was intermittent cloud. Starlit with running swell

force 3N Mod. SVVE, swell. Six ratings in the darkness of the T/S lay

awaiting the middle watch, 12 p.m. until 4 a.m. There came an almighty

explosion.

Hecla shuddered

and listed, a 21” port sub torpedo hit amidships (in the Navel reports

2 torpedoes, At 11 p.m. hit amidships. As a witness only one torpedo

hit the

Hecla a few minutes

after 11 p.m. putting the generators out of action, as the power went

off the ship. The ship was in total darkness. Action stations. (2 ZLB

pom-pom anti-aircraft, 6 x 4.5 guns, immobile for lack of power) We

were relieved of our station by regular trained RN Gunners. Being 3

watches only one watch manned guns and damage control etc. We were

ordered off the bridge of the ship and left without leadership. After

what seemed an eternity. The Hecla came on an even keel with no power.

She was immobile and drifting. My lifebelt would not hold oxygen, so I

went down below to mess deck 32 to try to find some authority that

could insure another life belt. There was no organisation below and I

was told to go and look around. Parts of the two watches were hanging

around not knowing what to do. There was no leadership. 839 crew

approximately 2/3 waiting for what? I roamed the lower deck finding

another air life belt. In looking for my life belt I came across 2

ratings of my mess 32. They were two regulars that could not read,

write or swim. They had been in the navy since the age of twelve. They

were cowed (never seen again). In the stokers mess there again were

nothing but the other watches hanging around.

At about 12.15 p.m. there was another explosion and I returned to

the upper deck. A second torpedo 21” hit under the starboard bow. There

was still no power with the ship dimly lit. I walked around checking on

mess deck mates. Several H.O’s (Hostility Only ratings) took the

place of the RN ratings missing from the pom-poms, operating the

pom poms manually. Everything was at a stand-still. I worked my way

back to the bow of the ship and befriended a regular Navy Able Seeaman

(AB)

throwing a rope off the bow. He stated “The next torpedo and over I

go.” He didn’t have long to wait. A third torpedo hit and most of the

crew abandoned ship as ithe command was peassd by word of mouth. The

Able Seaman said he would go over first and my mate was to follow. I

lowered

myself into the water to find my God-send waiting. Then we waited for

my friend to enter the water. He panicked screaming he could

not swim and would not release the rope. The AB told me to leave him

after swimming back twice. I had to get away from the ship. There was a

gapping

hole in the side of the Hecla’s bow. It took the AB and myself an

eternity to make headway. The ship was at an acute angle filling with

water and we were being dragged back into the ship. Then a forth

torpedo hit

and exploded and we were washed clear of the

Hecla. Following the AB we swam towards HMS

Marne, which was foolishly moving bow first to the

Hecla

in the starlight conditions. There were ratings climbing the nets on

the stern when a 21” torpedo blew the stern off. We were approximately

30 foot away. There was a blinding explosion and we were both stunned

and drifted with the swell.

After returning to my senses the AB said “We should leave the

Marne" and we swam away into the rolling swell. We thought the

Marne had had it. Then there came a fifth explosion in the direction of the

Hecla.

The water was alive with men hold ing onto debris and smashed life boats. We

swam into the swell again, coming from a northern direction. We came

across what looked like a sub’. Stopping we listened to voices calling

for the name of the ship in an American accent. I suggested going along

side but the Able Seaman said we were to get away as it would be

dangerous. We turned and swam in the opposite direction. We were

confronted with what turned out the be HMS

Venomous depth charging the area (the sub was attacking – surfaced).

Venomous was

depth charging amongst the survivors. Several floats crowded with

survivors came by but it was impossible to get a hold (oil was

everywhere). We carried on into the night. How long we swam could not

be recorded but the

Venomous

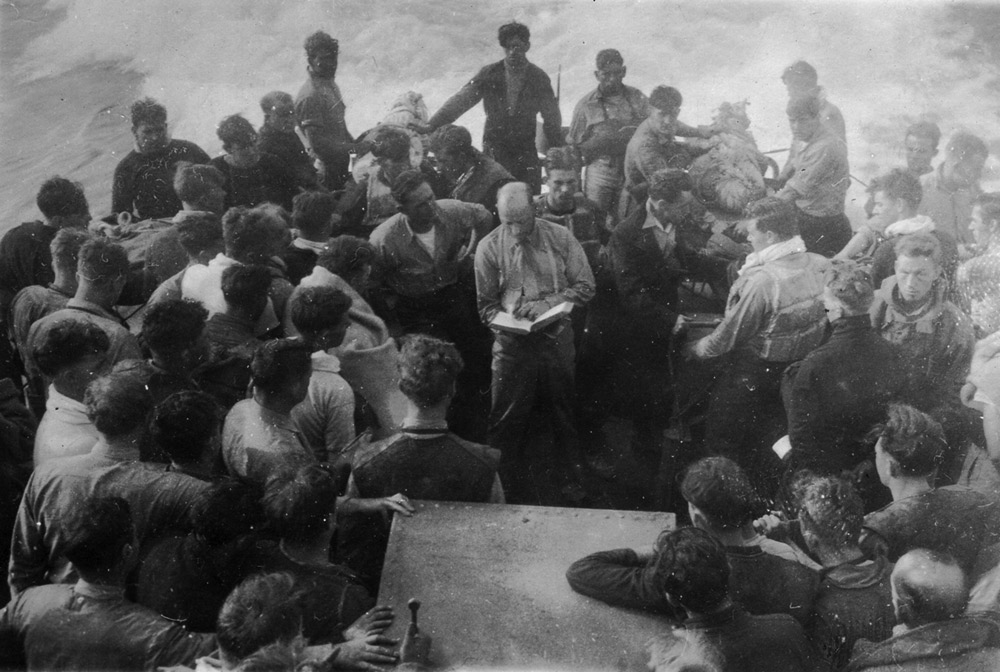

came into view, stopping to pick up a float full of men. She misjudged,

hitting the float and spilling the men to either sides of the ship. We

swam to the nets of the

Venomous on the stern and hung on being extremely exhausted. There came a voice from the bridge shouting “Let go AFT I have a ping”

Veromous

took off dragging us in the net. How long I was in the net I don’t know.

After screaming out I was untangled, dragged on board and thrown on the

deck. Afterwards thrown into the hammock rack in the seamen’s mess

deck to recuperate. When I came to I found myself lying alongside the

seaman friend that had refused to let go of the rope on the

Hecla.

He was raving mad. No one could do anything for him. We were told to

leave him he would recuperate. At first light I was helping to clean up

the mess on the quarter-deck near the nets when they pulled a body out

of the nets. It was the able seaman I had spent the night with. The

Venomous had something to answer for.

After picking up more men

Venomous became short of fuel and went along side of HMS

Marne with her stern blown off and milked for fuel. She then left the

Marne

and proceeded to Casablanca hoping Casablanca had been taken from the

Vichy French during ‘Operation Torch” North Africa. The reason for

going to Casablanca was that

Venomous hadn’t enough fuel to get to Gibraltar.

Venomous

at 12 knots stanchions cracked like B-gun firing. How men could take

such conditions is hard to understand. Water washed over the bows and

tore aft and into the seaman’s mess deck. Everything was wringing wet.

Her full speed 17 knots would have been a nightmare. We approached

Casablanca cautiously and a signal with authorities told us the

American’s had landed and were mopping up. We approached slowly to find

three USS ships, the flag ship of the American Med fleet USS

Augusta and aircraft carrier USS

Guadalcanal and a destroyer with a gapping hole in the bows. Tying up alongside to refuel the

Venomous

was invited to dine and everyone kitted up with clothing. Lunch, dinner

and breakfast. Then off to Gibraltar where we were invited into the

harbour and put aboard the battleship

King George V during the whole of the action I cannot remember seeing one officer. Not anyone above a petty officer.

The following day we were transferred to the

Stratheden, a liner, and put below with one officer off the

Hecla.

Below deck conditions were degrading with no sleeping facilities. We sailed

for England in a convoy. Two destroyers and one aircraft carrier. First

night out she exploded with loss of all the ships company

(approximately 1,200 dead). In the action “Operation Torch” North

Africa, approximately 17 Royal Navy ships (

Daily Express)

were put out of action. Survivors landed at Grenock Scotland and rekitted

with new gear, uniforms (basic), fed and transported back to Portsmouth

RN barracks. We were screened, paid money according to rank and given

28 days leave with no medical check for any lower deck personnel. That

night I blacked out finding myself in the wrong section of the

barracks. I slept on a form bench. I couldn’t recall how I got there. I

was walking around dazed. I found myself on a train to Birmingham but

not knowing how I got on the train. When I arrived home my mother had

been notified that I was missing believed killed in action.

The U-boat that sank the

Hecla and damaged

Marne was U-515 (Captain Lieutenant Henke) despite being engaged by B-gun on HMS

Venomous

and depth charged U-515 escaped unscratched. Anti-submarine forces

finally caught up with her on April 9th 1943 to the north of Madeira

Island where she was sunk by four USN destroyers and three aircraft from USS

Guadalcanal. Fourty-four of her ship company out of sixty, including her CO, were taken prisoner. I returned to HMS

Victory barracks after four weeks leave with my

Royal Oak

friend Pam. Pam was a survivor of the sinking of the

Royal Oak at Scapa Flow in the

Orkney Islands where nearly 900 men and boys were killed

in October 1939. The “Oak” was out of commission owing

to sea trials. Her gun’s shook her to pieces. On entering the main gate

Pam called back to me. He had had enough and decided to jump the wall. His nerves had gone and he was going to

friends in the north end of Portsmouth. Shaking hands I walked

into the barracks never to see him again. I was put in a mess deck,

allotted a hammock and slept and ate in a building 200 years old. After

one week I was transferred to Whale Island gunnery school for a course.

An antiaircraft gunner 3rd class. One week in barracks and no medical.

The barracks were full of war neurotics. No one wanted to know.

I arrived at Whale Island with a kit bag, a hammock and a case and on reporting to

a police officer was allotted a hut, mess and class and ordered to

double at all times between 8 a.m. – 5 p.m. No rating was exempt, if he carried

a kitbag he doubled. Things were bleak. Winter on Whale Island was

going to be bad. In the class of 35 we were allotted a chief petty

officer as a teacher who should have been in hospital. He had been

wounded while serving on the battleship HMS

Prince of Wales, when she engaged the German battleship

Bismarck.

He had been trapped in a section of the ship sealed off to stop the

ship sinking. In the same action with

Bismarck the battleship HMS

Hood with

a crew of 1,400

was hit with one salvo and three men swam away from her.

One Midshipman (officer) two ratings from the lower deck.

The midshipman was mentioned in dispatches.The lower deckmen

were not named or mentioned. The midshipman was killed in a sports car

going on leave (survivors) at Whale Island.

I continued my gunnery

course; an incident with the chief petty officer. The class of 35

doubling (running from clas to parade ground) was accused of

“shufferling” (half a run) and I being nearest to the chief

petty officer was kicked in the backside. I jumped out of ranks and

kicked him back in the backside. He threateded to report me to the

Commanding Officer. Another rating witnessed what happened. I had a

witness

against him and he dropped the charge. The following day the witness

who spoke up for me was transferred to Combined Operation for three

months on minor landing craft 25

ft in length. Then to major 110 ft landing craft with Mountbatten's

death squad [

Mountbatten's reputation was damaged by the the disastrous raid on Dieppe in August 1942]. I did my first three months at Qeenscliff, Dartmouth for

the Royal Navy’s Officer College. I did thirteen landings in the

American sector and one in Aremanches (British sector).

On being demobbed I was questioned about my physical condition. I

reported that I had lost the top joint of the little finger on my

right hand and was told I could receive £14 but would have to stop in the Navy

for a further three months. I refused and was demobbed. I

was ashamed of my condition and did not report that I was “bomb happy” and was looked after since by my wife, not

claiming until 1992.

Combined Operations and the D Day Landings in Normandy

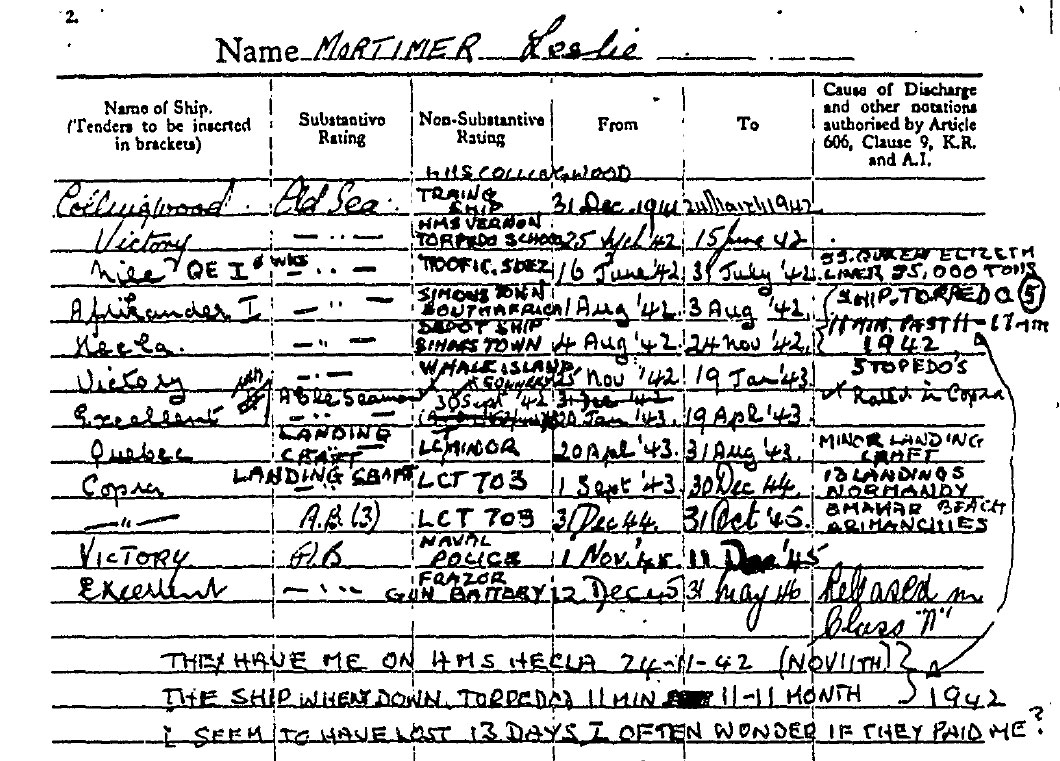

Les Mortimer helpfully but confusingly inserted his own additions to his official Service Certificate:

After survivor's leave Les

Mortimer was sent on a course at HMS Excellent, the Gunnery School on Whale

Island at Portmouth, and then joined HMS Quebec,

a Combined Operations training base for the LCT (Landing Craft Tanks)

on Loch Fyne in western Scotland in preparation for the landings in Normandy.

The LCT and the Landing Ship Tanks (LST) which brought them across the

Atlantic from the east coast of America where they were built were the

key to the success of the D Day landings but they were

brutes to control and had no accommodation aboard for their crew.

HMS

Copra (an acronym for Combined Operations pay, ratings and accounts) was a

shore base staffed by Wrens at Largs on the Clyde which processed the

pay

and allowances of Royal Navy personnel in Combined Operations.

Les Mortimer added LCT 703, the name of the LCT in which he

served, alongside HMS Copra on his Service Certificate but despite being a shore base the name of HMS Copra is engraved on many of war graves in Normandy.

This photograph of the USN Landing Craft heading for Omaha Beach on 6 June 1944 with the USS

Augusta in the background was scanned from a French postcard belonging to Les Mortimer but is also on the front cover of

The U.S. Navy at Normandy: Fleet Organization and Operations in the D-Day by Greg H. Williams ( McFarland, July 2020).

30 ft LCVP (Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel) (Higgins Boats) heading for Omaha Beach on 6 June 1944

In the background is the cruiser USS Augusta, flagship of the Western Naval Task Force

30 ft LCVP (Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel) (Higgins Boats) heading for Omaha Beach on 6 June 1944

In the background is the cruiser USS Augusta, flagship of the Western Naval Task Force

Sixteen months earlier on 13 November 1942 HMS Venomous had berthed alongside the USS Augusta at Casablanca and the USN had fed and clothed the survivors from HMS Hecla

Scanned from a postcard belonging to Les Mortimer

There were two LCT 703. LCT 703

was an American LCT with a USN crew which was sunk on D Day but Les

Mortimer served in HM LCT-703, a British Landing Craft Tank in 57 LCT

Flotilla (known as the 57 'Heinz'), part of Q LCT Squadron (Senior

Officer Lt Cdr Arthur Duncan Stather Dunn) based at Plymouth. QLCT

Squadron operated with B Force, the follow-up force for the

American beaches in the west including Omaha, the most fiercely

defended of the five beaches. He joined HMLCT 703 in September

1943 and "did thirteen landings in the American sector and one in

Arromanches (British sector)". Click on this link to see the

stowage plan for LCT-1097,

an addendum to the orders for Force G (

IWM Documents.9372). This would be

similar to that for LCT 703 and included three cruiser tanks.

Julie Nestic identified her maternal grandfather, Les Mortimer,

in the photographs of the crew of HM LCT-703 below. If you recognise a

family member who served in HM LCT-703 during the Normandy landings

please

e-mail Bill Forster so that he can add his name to the caption

Les Mortimer is second from left in this photograph which may have been

taken during training on another landing craft berfore he joined HM

LCT-703

Taken on the bridge at the stern - note the funnel

Les Mortimer is second from

right in this photo of LCT 703 on on her way to Normandy on

5 June - but who are the other crew members?

Les Mortimer is second from

right in this photo of LCT 703 on on her way to Normandy on

5 June - but who are the other crew members?

The Sub Lt in the RNVR on the left and many others are in both photos but have not been identified

Bad weather forced the postponement of the D Day Landings to 6 June

Photograph courtesy of Julie Nestic, grand daughter of Leslie Mortimer

I

am hoping to receive more details of this period in Les

Mortimer's life from his family but in the meantime click on the link

to see

the Admiralty Green List (ADM 210) of LCT in Q LCT Squadron (revised

weekly) and read the account of Austin Prosser who joined the Navy as

an Ordinary Seaman in 1942 and by 1944 was First Lieutenant in HM Landing Craft Tank 1171 part of LCT Flotilla 57

which included Les Mortimer's LCT. His irreverent attitude frequently

got him into trouble with authority but makes for an amusing read.

"We

had an extremely rough trip [from Oban] to Plymouth during which we

discovered what a battering our ship could take. Some ships had faired

less well and others had been lost. In Plymouth we learnt that we were

to be attached to the American forces. A near mutiny was threatened

when American senior officers visited our ship to explain the

implications of our attachment to their Navy. There must have been many

important operational matters discussed but amongst it all was a ban on

alcohol to bring us into line with the US Navy 'dry ships' policy. This

immediately captured our attention and there was uproar! After a lot of

discussion, and a few diplomatic moves to keep the peace among the

Allies, it was decided that nothing should change. In the event it was

a popular outcome for everyone since the Americans spent a fair amount

onboard helping us deplete our stocks of drinks in case, as was

expected, we would be on a one-way mission!

More

training and routine maintenance on board followed and we had some

large folding extensions fitted to our bow door to make it easier to

unload vehicles on the beaches. Then the time came for our flotilla,

the 57th (otherwise known as the 57 'Heinz') to take on board our cargo

at St Johns on the south (Cornish) side of the Tamar River. We loaded

six Sherman tanks, six half-track ammunition lorries, two half-track

ambulances and all their crews. Our ship was now rather overcrowded.

At

this late stage we finally found out where we were going and what was

expected of us - we had to deliver our precious cargo onto a beach

codenamed Omaha in Normandy..." click on this link to continue reading Lt Austin Prosser's account.

Prosser's LCT broke in two and sank while returning from Omaha Beach in October.

The Pennant Numbers of LCT 2313 and LCT 2479 are visible in this photograph taken at Antwerp after the clearing of the Scheldt estuary

The Pennant Numbers of LCT 2313 and LCT 2479 are visible in this photograph taken at Antwerp after the clearing of the Scheldt estuary

Written on reverse by Les Mortimer: - "Two Mark V: loaded with NAAFI goods. Antwerp."

"The Arromanches Mulberry remained open

well into the autumn for although Le Havre and Antwerp were captured

during the first half of September, neither could be reopened until

November, the former because demolition, by the RAF as well as the

retreating Germans, had been so comprehensive and the latter because

the heavily-mined approaches to the undamaged port were dominated by

enemy-held territory, necessitating a further major amphibious

operation (the invasion of Walcheren), followed by a major mine

clearance operation before the first cargo could be delivered. Antwerp's docks were the largest in Europe with a daily

capacity of 40,000 tons and were opened to large ships on 28 November 1944 and, thereafter became the principal Allied supply

port for the advance into Germany."

Operation Neptune: The Normandy Invasion, D-Day 6 June 1944 (Naval Historical Branch).

The

Clearing of the Scheldt Estuary and the Liberation of Walcheren

between 2 October – 7 November 1944 which opened up Antwerp’s port to Allied

shipping is described in a commemorative booklet pubished by the COI for the Ministry of Defence on the

60th anniversary of the end of the war which can be read online as a

PDF by clicking on the link.

***************

Emigration to Australia

After the war Les Mortimer returned to Britain and worked at Austin

Motors' Longbridge plant at Oxford before

marrying and emigrating

to Australia:

"he

married Edna Nash (my beautiful grandmother) on 12 Feb 1946 at Kings Norton Church

Birmingham and was released from the Navy four months later on 31 May

1946. He moved to Australia in 1949 after my mother, Janet Mortimer,

was born in

1947" (Julie Nestic, his Grand-daughter).

In 1998 when Les wrote the account of his rescue from HMS Hecla he was living in an outlying district of Melbourne near where his children and grand children lived. Leslie Mortimer was 92 when he died in 2016.

A second daughter, Carol Tregonning (nee Mortimer), was born in Australia and is alive today:

"Dad

was a very quiet man and pretty private about his tragic experiences.

He suffered from bouts of manic depression all his adult life and I’m

sure the hardships that he went through contributed to this. Dad's

funeral was on 11. 11. 2016. It wasn’t planned for that date. Just a

date I chose at random. Only after did we realise that it was the

anniversary of the sinking. A very strange occurrence. Mother told me

she received a telegram informing her that Dad had died in action. He

later turned up on her doorstep. That must have been a big shock for my

Mother."

Sadly, Carol has no contact with his family in England and I am hoping that they will read his story here and get in touch with me by e-mail

The Last Man Standing?

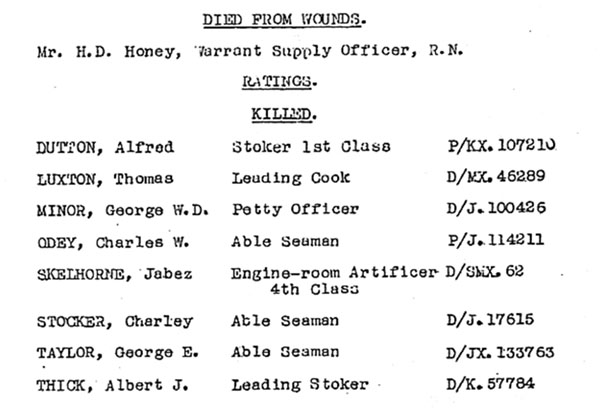

There were 858 officers and men aboard Hecla

when she was torpedoed and 282 names on the list issued by the

Admiralty of those who died. I have traced the families of less than a

hundred and non of them are alive today but the publicity the death of

Reg Bishop on 4 June 2022 received in national newspapers (The Sun, Express and Mirror

on 17th June and the Daily Mail online 17th June) may lead to me being

contacted by the family of an elderly survivor before this year's 80th

anniversary of the loss of HMS Hecla on 11 November 2022, Armistice Day.

Leslie

Mortimer was one of eleven children of Rowland Mortimer, a mattress

maker, and his wife Emily May (nee Flynn). He was born at Kings Norton,

Birmingham, on the 24 November 1923

and trained as a bench fitter (drilling machine operative). He gave his

mother as his nearest relative when he enlisted in the Royal Navy aged

eighteen in December 1941.

Leslie

Mortimer was one of eleven children of Rowland Mortimer, a mattress

maker, and his wife Emily May (nee Flynn). He was born at Kings Norton,

Birmingham, on the 24 November 1923

and trained as a bench fitter (drilling machine operative). He gave his

mother as his nearest relative when he enlisted in the Royal Navy aged

eighteen in December 1941.

Charley - not Charles -

Stocker was born at Uplyme near Lyme Regis on the Devon Dorset border

on the 28th June 1896 and was probably the oldest rating in Hecla when she was torpedoed. He left school at 14 and went into domestic service at the nearby village of Whitchurch Canonicorum.

Charley - not Charles -

Stocker was born at Uplyme near Lyme Regis on the Devon Dorset border

on the 28th June 1896 and was probably the oldest rating in Hecla when she was torpedoed. He left school at 14 and went into domestic service at the nearby village of Whitchurch Canonicorum.